This essay originally ran on Mujeres Talk on March 25, 2013. We are posting it again today on June 24, 2014 to offer another perspective on immigration and in recognition of a season when many are now engaged in travel for research.

By Catherine S. Ramírez

Many years ago, a family I knew—let’s call them the Pedrazos—invited their parish priest to their home for dinner. Like many Mexican Americans, the Pedrazos were Catholic. Their priest was from Spain. In all likelihood, he’d been assigned to their church to attend to its many Spanish-speaking parishioners. The Pedrazos made tamales for him, a sign that they held their guest in high esteem, as tamales require a fair amount of work and Mexican Americans generally serve them on special occasions. As I picture them readying themselves and their home for their visitor, I imagine Mrs. Pedrazo spreading the creamy masa and spicy meat filling over the wet cornhusks and carefully folding the ends of each hoja to create a tidy bundle. I picture scores of tidy bundles. Then I imagine the astonishment, disappointment, injury, and anger she and her husband felt when their guest refused to eat the meal she had prepared for him. “No como comida de therdos,” the priest announced in his Castilian accent. Since the tamales were made of corn and pigs eat corn, he wouldn’t touch them.

Today, it appears Spaniards’ attitude toward Mexican food has changed. In 2009, the New York Times’ Andrew Ferren surveyed a handful of Mexican restaurants in Madrid and concluded that Spaniards had “come a long way in embracing the food of their former colonies.”[1] The 2013 Páginas Amarillas, Madrid’s equivalent of the Yellow Pages, lists 103 Mexican restaurants. 11870, an online restaurant reservation service that functions somewhat like Open Table, tallies 104.[2] The Spanish capital also boasts 85 Argentine, 38 Peruvian, 27 Cuban, 23 Colombian, 21 Ecuadoran, ten Venezuelan, four Uruguayan, and three Chilean restaurants, not to mention 20 restaurantes sudamericanos.[3] Stores specializing in productos latinos, like Paraguayan yerba mate and mixes for arepas, savory Colombian cornmeal patties, dot the city. [Fig. 1]

Chirimoyas, a sweet, succulent fruit native to the Andes, can be found in just about any frutería. And many supermarkets have a small section devoted to Mexican food, complete with flour tortillas, ready-made guacamole and salsa, and kit fajitas. [Fig. 2]

Without a doubt, the fruits of empire are available in Madrid in huge part because of the movement of Latin Americans to the former metropolis. According to a report published in 2010 by Network Migration in Europe, a Berlin-based think tank devoted to the study of migration and integration, a total of 2,365,364 people of Latin American origin lived in Spain in 2009. Latin Americans comprised 37 percent of the foreign-born population, up from 24 percent ten years earlier. Most hail (in numerical order) from Ecuador, Colombia, Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru.[4] Relatively few are from Mexico, but of all the cuisines from Spain’s former colonies, Mexican seems to be the most prevalent and popular. Why?

As the American daughter of a Mexican immigrant who won the Los Angeles Times Best Home Cook of the Year Award in 1992, my response to this question is a simple duh: Mexican food is prevalent and popular in Madrid and many other places simply because it’s tasty. This is a glib, not to mention biased, answer. There are many reasons for the increasingly global demand for Mexican fare. Like German, Italian, and Japanese cuisines in the United States (think hot dogs, pizza, and sushi), Mexican food has been assimilated, in the literal and sociological senses of that word. For evidence of its absorption by and emanation from the American mainstream, one need only look at the proliferation of the Denver-based chain, Chipotle, which lays claim to restaurants in the US, Canada, the United Kingdom, and France.[5] Despite atrocities “The Great Satan” has committed and continues to commit at home and abroad, Americana, be it in the form of jazz, Disney, Starbucks, or Mission District-style burritos, retains its allure in many places. According to Gustavo Arellano, author of Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America, Mexican fare has even made it to outer space. Since 1985, NASA has catapulted its astronauts into space with tortillas, which have proven more durable and less dangerous to sensitive equipment than bread.[6] Tony restaurants like Chicago’s Topolobampo show that Mexican food has also drifted from its humble origins. In 2010, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization declared “traditional Mexican cuisine,” along with “the gastronomic meal of the French” and “Mediterranean diet,” an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This was the first and only time food made UNESCO’s privileged list.[7]

When I moved to Madrid in August of 2012, I was intrigued by the Mexican restaurants here and took it upon myself to eat in as many as possible before my return to the US the following year. How is the Mexican gastronomic experience reinterpreted in its new surroundings, I wondered? More concretely, who owns, works in, and patronizes Mexican restaurants in Madrid? And what can the migration and assimilation of Mexican food tell us about the migration and assimilation of people, both in the US and elsewhere? Along with an empty stomach, a full wallet, and an increasingly crammed notepad, these are some of the questions with which I’ve set out as I’ve explored Mexican cookery in my adopted city.

Like images of the Virgin Mary in tree trunks, Mexican eateries in the US tend to reflect migration patterns and shifting demographics. However, the ones in Madrid—and, here, I’d wager to say in just about any other European city—testify more to that city’s elite cosmopolitanism. In other words, Mexican restaurants in Europe signal the presence of American expats and/or well-heeled foodies. By and large, the Mexican restaurants in Madrid have a trendier or more upscale air than their Latin American counterparts, many (but certainly not all) of which appear to be run by and for hardworking and thrifty immigrants. For example, at Hatun Wasi, a Peruvian restaurant that recently opened in the working-class, immigrant neighborhood of Cuatro Caminos, the no-nonsense dining room consists of mismatched chairs, tables, and barstools. The floor is clean, but scuffed. A simple blackboard in the window announces the restaurant’s hours and the prices of various specials. [Fig. 3]

A two-course menú del día or lunch special costs a mere three euros (around four dollars). In contrast, Takeiros, a Mexican restaurant near my apartment in the middle-class neighborhood of Ríos Rosas, offers a three-course menú del día for 11 euros (roughly 14 dollars). Dinner runs around 30 euros (40 dollars), a hefty price for many madrileños, immigrant and native-born alike, in this moment of economic crisis. Where Hatun Wasi is a modest, if not barebones, joint, many Mexican restaurants in Madrid are bedecked with colorful decorations that scream ¡MÉXICO! (or, as the Spaniards spell it, Méjico), such as papel picado, serapes, and lucha libre masks. At Takeiros, Mexican lotería cards cover the walls and metal tooling lampshades dangle from the ceiling. [Fig. 4] And except for the live mariachi music Thursday nights at La Herradura, one of Madrid’s more established Mexican eateries, salsa music dominates the playlists in the Mexican restaurants I’ve patronized here.

All the meals in these restaurants begin with a small basket of totopos (what Spaniards mistakenly call nachos) and salsa. The chips always taste a bit like reconstituted cardboard, a travesty given the ubiquity of mouthwatering fried food in Spain, most notably, churros, patatas fritas, and calamares a la romana. And while the salsa, be it red or green, is usually flavorful, it’s never spicy enough for me. Still, despite their less-than-promising start, the Mexican meals I’ve had in Madrid have been surprisingly satisfying. I’ve enjoyed fresh green salads garnished with velvety avocados and tangy flores de jamaica. Staples, like quesadillas, burritos, and flautas, can be found on nearly all menus. However, unless I’m at a burrito or taco bar, I usually don’t bother with the more prosaic foods. Instead, I go for more complex dishes, like pollo en mole poblano, cochinita pibil, and albondigas con salsa de chipotle. [Fig. 5] Mexican beers, such as Corona and Pacífico, are widely available; Mexican sodas and aguas frescas, less so. Impressively, Takeiros’ wine list consists exclusively of wines from Baja California.

A couple of Mexicans opened Takeiros in 2011. They own three other eateries in Madrid, one of which, a take-away counter, also specializes in Mexican fare. While the customers at Takeiros appear to be mostly Spaniards, the workers I’ve encountered there have all been immigrants. Peruvian and Ecuadorian chefs have prepared my food to perfection and Argentinian and Mexican waiters have delivered it to me and put up with my many questions. The dishwasher, like the waitress I photographed in front of Hatun Wasi, is a young immigrant from Romania.

I’ll wrap up with a brief discussion of Romania, what I’ve come to see as the Mexico of Europe. Just as Mexico hitched its cart to the NAFTA horse in 1994, Romania, one of Europe’s poorest nations, joined the European Union in 2007. While NAFTA failed to provide for the free movement of workers across Mexico, the US, and Canada, EU membership has allowed Romanians to move and work within member states. Like many Mexican migrants in the US, many Romanians came to Spain, Europe’s leading country of immigration from 2000 to 2007, to work in the then booming construction, tourism, hospitality, and domestic-service industries.[8] In 2008, they surpassed Moroccans as the largest foreign group in this country.[9] Then Spain’s economic bubble burst and unemployment skyrocketed. The Spanish government responded by trying to restrict Romanian immigration, a reversal of its commitment to admit rumanosas fellow members of the twenty-seven-nation EU.[10] More recently, the prospect of Romanians and Bulgarians being able to work freely in the UK starting in 2014 has provoked protests in that country.[11] To deter “an influx of unwanted people,” the UK’s equivalent of the Department of Homeland Security, the Home Office, has considered launching an advertising campaign in Romania and Bulgaria stressing Britain’s less attractive qualities, like its notoriously bad weather.[12] Hardy, despised, feared, and here to stay, Romanians, not unlike Mexicans in the US, are the cockroach people of Europe.[13]

In physiology, assimilation refers to consumption and the body’s absorption of nutrients after digestion. Like the Spanish priest who rejected the Pedrazos’ homemade tamales, Europe refuses to take in Romanians or to absorb what many of them have to offer: their labor. Indeed, it sees them as a contaminant, as the recent scare over horsemeat fraudulently labeled as beef has made patent. When horsemeat was first discovered in frozen lasagna in British and French supermarkets earlier this year, Romania was immediately cast as the culprit. French and British news media reported that new traffic laws banning horse-drawn carts in that country had led to the mass slaughter of horses and the subsequent introduction of horsemeat into the food chain. Even though the horsemeat was ultimately traced to a factory in southern France, the perception of Romania as dirty, primitive and, therefore, thoroughly un-European endures.[14]

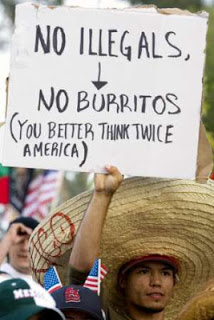

A Spaniard in LA. Chicken mole, Romanian workers, and a Chicana scholar in Madrid. Lasagna in France and Britain. Clearly, people and food travel. Far too often, the latter goes down more easily than the former, as the sign in the final illustration I’ve included in this essay indicates [Fig. 6].[15] Whether or not people assimilate and are assimilated—incorporated, integrated, welcomed—depends on numerous factors, including access to citizenship and basic social services, particularly education and health care, possession of rights and protections as workers, and genuine tolerance and respect.

Catherine S. Ramírez, an Associate Professor of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, is spending her sabbatical year in Madrid, where she’s writing a book tentatively titled Assimilation: A Brief History.

[1] Andrew Ferren, “Mexican Hot Spots in Madrid,” New York Times, May 5, 2009, http://intransit.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/05/mexican-hot-spots-in-madrid/ (accessed March 18, 2013).

[2] http://11870.com/k/restaurantes/es/es/madrid (accessed March 19, 2013).

[3] http://madrid.salir.com/restaurantes (accessed March 18, 2013).

[4] Trinidad L. Vicente, Latin American Immigration to Spain, http://migrationeducation.de/48.1.html?&rid=162&cHash=96b3134cdb899a06a8ca6e12f41eafac (accessed March 18, 2013).

[5] “Chipotle Opens Restaurant in London, First in EU,” Denver Business Journal, May 10, 2010, http://www.bizjournals.com/denver/stories/2010/05/10/daily4.html (accessed March 19, 2013).

[6] Gustavo Arellano, Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America (New York: Scribner, 2012).

[7] http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/index.php?lg=en&pg=00011 (accessed March 18, 2013).

[8] Michael Fix, Demetrios G. Papademetriou, Jeanne Batalova, Aaron Terrazas, Serena Yi-Ying Lin, and Michelle Mittelstadt, Migration and the Global Recession: A Report Commissioned by the BBC World Service (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2009), 33-34. Also see http://www.migrationpolicy.org/pubs/mpi-bbcreport-sept09.pdf (accessed March 19, 2013).

[9] Ibid., 38.

[10] Raphael Minder, “Amid Unemployment, Spain Aims to Limit Romanian Influx,” New York Times, July 21, 2011, http://travel.nytimes.com/2011/07/22/world/europe/22madrid.html (accessed March 19, 2013).

[11] Stephen Castle, “Britain Braces for Higher Migration from Romania and Bulgaria,” New York Times, March 4, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/05/world/europe/britain-braces-for-higher-migration-from-romania-and-bulgaria.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 (accessed March 19, 2013).

[12] Sarah Lyall, “Welcome to Britain. Our Weather Is Appalling,” New York Times, January 29, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/30/world/europe/welcome-to-britain-our-weather-is-appalling.html (accessed March 19, 2013).

[13] I take the term, “cockroach people,” from Oscar Zeta Acosta’s 1973 novel The Revolt of the Cockroach People (New York: Vintage, 1989).

[14] Andrew Higgins, “Recipe for a Divided Europe: Add Horse, Then Stir,” New York Times, March 9, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/10/world/europe/recipe-for-divided-europe-add-horse-then-stir.html?pagewanted=all (accessed March 19, 2013).

[15] This image is from http://imageshack.us/photo/my-images/74/r2048252209bz4.jpg/sr=1 (accessed March 19, 2013).All other photos here were taken by the author.

!["Zine Study XIV: [language]" Photo by Flickr user Shawn Econo. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0](/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/149172094_f4a814bf30_z-350x239.jpg)