by Paloma Martinez-Cruz

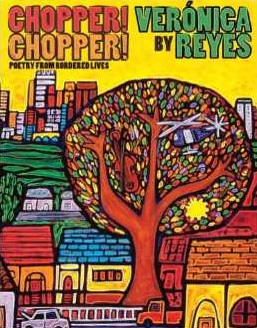

Verónica Reyes. Chopper! Chopper! Poetry from Bordered Lives. Pasadena, CA: Arktoi Books, 2013. 111 pages. ISBN 978-0-9890361-0-8. $18.95

I left my hometown of Los Angeles to attend college in the Bay Area, and then I left California altogether to attend graduate school in New York City. Many denizens of the San Francisco Bay and the five boroughs of New York City have no love for my birth town, so when people asked me where I was from, I felt shy about admitting I was from the place known as “72 suburbs in search of a city.” One day a fellow student shared with me what he loved about it: “You can feel how it’s red and brown.” After he said this, I realized that he was right, and that so many of the quips about L.A. being anti-intellectual and superficial were, in truth, about the other L.A., the tinsel L.A. that eclipses our red and brown realities, until violence erupts in the streets, or Chicana feminist jota poets like Verónica Reyes sound the thunder of our lives in verse.

I left my hometown of Los Angeles to attend college in the Bay Area, and then I left California altogether to attend graduate school in New York City. Many denizens of the San Francisco Bay and the five boroughs of New York City have no love for my birth town, so when people asked me where I was from, I felt shy about admitting I was from the place known as “72 suburbs in search of a city.” One day a fellow student shared with me what he loved about it: “You can feel how it’s red and brown.” After he said this, I realized that he was right, and that so many of the quips about L.A. being anti-intellectual and superficial were, in truth, about the other L.A., the tinsel L.A. that eclipses our red and brown realities, until violence erupts in the streets, or Chicana feminist jota poets like Verónica Reyes sound the thunder of our lives in verse.

The poems in Chopper! Chopper!, Reyes’ first published collection, envision East L.A. as the continuity of Mexican experience, participating fully in an Americas-based spirituality that venerates the natural world. As with physical sacred gatherings, the volume begins with a blessing. The poem “Desert Rain: blessing the land” [sic] surveys the desert cityscape with devotion.

The agua took her back to her childhood in México

rain that blessed her alma como copal shrouding her skin

She inhaled the desert aroma over concrete, nopales,

and limones beneath splintered street telephone wires

Socorro breathed in once and inhaled México in East L.A.

While I am exhilarated by the red and brown affirmation of Mesoamerica in Los Angeles, some of the portraits of Chicana ethnicity in this volume echo others. From my perspective as a Latin American/Latina Studies scholar, I question what seems like a nostalgia that conflates spirit, nature, and nation. Although some of the poetic turns tended toward predictability, there is also much to recommend in this volume. Reyes is at her best when she navigates the difficulty of voicing bicultural, transnational experience by moving in for the hyper close-up, telling us what she alone is capable of observing. In “Theoretical Discourse over ‘Sopa’ (what does it really mean?),” she playfully employs academic jargon to try to make sense of a word that has multiple meanings.

All our lives we called it “sopa”

Differentiated “sopa” from fideo

to estrellas or melones

labels for different pastas

titles to establish subjectivity

within the hegemonic world of pasta.

The poem concludes with the narrator and her sister agreeing to use the word sopa the same way that their mother had used it – to refer to Mexican rice – thereby legitimizing local, intimate knowledge over official language usage.

As in the postmodern approach to “sopa,” Reyes’ poetry consistently repositions authority so that cholos, jotas and bus patrons are key culture makers. In “Super Queer,” the queer Chicana becomes a supernatural champion, managing to survive homophobia, bashing and “what you thought no human being can withstand.” Where others are tempted to perceive marginalization or victimization, Reyes tells of pride and strength, urging the listener to “take off those silly straight lenses that skew your vision.” In “El Bus,” the narrator is proud to announce, “I speak in bus routes,” which, as Angelenos and visitors to the city are aware, is a dialect spoken almost exclusively by the poorest of the poor. In Reyes’ poem, the speaker claims “You got it, esa or ese, I know the system/It’s in my blood to travel the calles via el bus” as if to boast of royal lineage. Reyes’ poems invert the parameters of social inclusion, so that queer and street folk decide who belongs, and misguided wearers of “silly straight lenses” and novice bus riders become the outlanders in need of charitable assistance.

Vehicles of surveillance and pesticide application populate Reyes’ poetic universe, producing a bellicose environment in which East L.A. residents are surrounded by drone-like aerial hostility. “Green Helicopters” describes the apple-orchard helicopter that sprays toxins on the migrant workers, and “Chopper! Chopper!” depicts the play of young neighborhood children who turn the menacing sounds and lights of police helicopters into fantastic games.

The cops announced to the convict, “We know where you are. We know…”

And Xochitl ran out of breath chasing the big white light piercing the darkness

She stopped and stared up at the helicopter slicing the chapopote sky for a moment

It was almost as if it were stuck like the mammoths, the saber-toothed tiger, the Chumash

woman whose bones remained deep underground until the archaeologist came

The people screamed and wailed to be set free from the tar that pulled them down

that swallowed them little by little as they struggled to get out from the bottom

Still the thick goo engulfed them hole suffocating their skin, filling their mouths

Xochitl’s brown eyes stared at the chopper swirling in East L.A.’s summer sky

But the helicopter broke free, pulled back its white light and flew away to the hill

Here, the child Xochitl plays under a tar firmament where the craft hovers like a relic from California’s Pleistocene epoch, witnessing centuries of ancestors struggle against asphyxiation across the sky: just another summer night in East L.A.

While most of Chopper! Chopper! must remain unexamined here, there can be no doubt that Reyes achieves what she sets out to do. In her poem “A Xicana Theorist,” her queer protagonist moves through a lesbian, Latina social space, and yet she poses the question, “Are we really safe?” The final verse reveals the highest potential that theoretical work can aspire to achieve.

She dances with the woman from the bar

She holds her gently around the waist

She leans her body closely into hers

She wants to cry and tell her she is hurt

…tell her she is tired of fighting

…tell her she feels alone and scared

She wants to heal her wounds

These last lines of “A Xicana Theorist” leave room for interpreting whether the wounds she wishes to heal belong to her or to her dance partner, and this blurring of bodily boundaries and subjects allows the reader to interpret a more expansive notion of selfhood that includes all the Latinas who are wearied by building their lives in spaces that are racially negative and sexually oppressive. The desire that is repeated in these last lines does not hone in on sexual appetite, which would make sense given the erotically charged environment of the bar, but rather emphasizes the act of telling. The telling is the medicine the poetic voice craves in order to heal wounds.

In the tar and asphalt prism of East L.A., Reyes’ poems unearth and celebrate centuries of red and brown truths. While some of the writing resorts to idealizing Mexico as a font of political and spiritual alignment, the collection convinces readers to rethink urban spaces and witness the cunning and courage that develop under a dome of both hyper vigilance and civil neglect. In the midst of roaring engines, slicing blades and hostile surveillance lights, her courageous act of telling manages to cultivate a space of safety and healing: a place for pride to grow.

Paloma Martinez-Cruz, PhD, works in the areas of contemporary hemispheric cultural production, women of color feminism, performance and alternative epistemologies. She is the author of Women and Knowledge in Mesoamerica: From East L.A. to Anahuac (University of Arizona Press, 2011) and the translator of Ponciá Vicencio, the debut novel by Afro-Brazilian author Conceição Evaristo, about a young Afro-Brazilian woman’s journey from the land of her enslaved ancestors to the multiple dislocations produced by urban life. Martinez-Cruz is also the editor of Rebeldes: A Proyecto Latina Anthology, a collection of stories and art from 26 Latina women from the Midwest and beyond. Currently Martinez-Cruz is at work on a book publication examining the resistance fronts found in Chicano/a popular culture. [5/1/14 post updated to correct an editorial error]