By Prof. Oriel María Siu

Oriel María Siu is Assistant Professor and the founding Director of Latino Studies at the University of Puget Sound.

(This is a copy of the Keynote speech I gave at the University of Puget Sound’s Graduates of Color Ceremony in May 2015. I dedicate it to all students of color at this and any other institution of higher learning in the U.S.)

As people of color, you were never meant to be at a university. I was never meant to teach at one. And your family and I were never meant to be here celebrating your graduation today.

The establishment of universities you see, were a direct result of the European colonization of the Americas and later white settler expansion all over the globe, a process begun in 1492. From the beginning, universities served as a crucial tool for the introduction and retention of a white Eurocentered power structure in these occupied territories. In the Americas, universities were created and run by British and Spanish settlers and later by their descendants for the purpose of founding and retaining the colonial order of things. The founding years of the first universities in this continent should therefore be no surprise; they directly paralleled the English and Spanish processes of colonization north, center, and south: the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (1538), Universidad de San Marcos of Perú (1551), Real y Pontificia Universidad de México, today the UNAM (1551), and Harvard University (1636), to name but a few.

Through savage processes of forced displacement, genocide, racialization, and the enslavement of Natives and Africans, whites self-proclaimed themselves superior to other people upon entering the Americas. From 1492 to 1592 –or the first 100 years of the occupation alone– it has been estimated that Europeans decimated more than 90 million indigenous people in the Americas, making it the bloodiest holocaust in the history of human kind (other estimates place this number above the 100 million people mark). Aside from this genocide, more than 11 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic, with death rates so high during that atrocious Middle Passage that many lives were lost at sea. Engendered by a system of slavery and the decimation and removal of Native life, the colonial order of things in the Americas consisted of the formation of a particular economic system; one which controlled, confiscated and reserved productive Native lands for the use of the white settler; one which ensured the flow of exploitable, cheap and free labor for the occupiers’ benefit; and one which ensured little to no upward mobility for the colonized. Universities, as I was saying, were crucial to the retention and functioning of this colonial order.

As spaces for the creation and retention of systems of thought, universities contributed to the eradication of indigenous educational institutions and to the displacement, invalidation, destruction, and subalternization of indigenous and African ways of knowing. In the minds of missionaries and “men of letters” –as scholars were called back then–, indigenous knowledges were dictates of the devil and thus had to be disciplined, punished and eliminated. These knowledges and epistemologies neither corresponded to the history of the so-called West the colonizers imposed here in the Americas nor were they recognized as valid or beneficial to the colonial system. Native knowledges did not support racial, class nor gender hierarchies –all organizing principles of colonial America. As Duwamish Chief Seattle said to the settlers that later appropriated his name and this land in the Northwest, Native ways did not see land as belonging to people as the white man understood it, but rather that people belonged to the land. As sites for the development and preservation of ideology, universities thus became the mechanism through which these indigenous knowledges were made inferior and obsolete by the white colonial settlers, replaced instead with Eurocentric lenses of the world. These new lenses were channeled through the academic disciplines that universities engendered –Math, Sciences, Humanities and Philosophy– disciplines all designed to rationalize the Eurocentric white power structure in place still to this day.

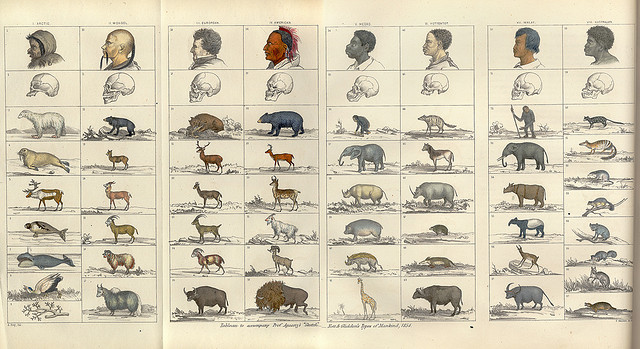

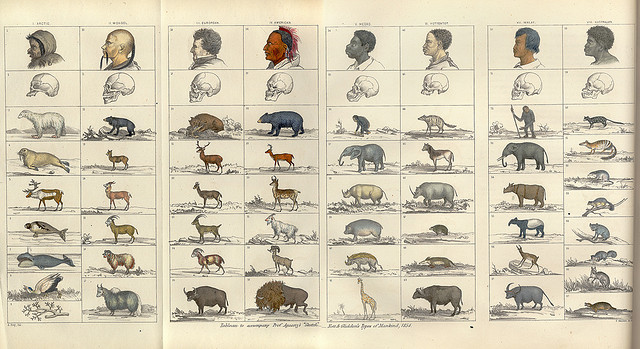

From Types of Mankind (1854) by J.C. Nott, and Geo. R. Gliddon. In arguing for the superiority of whites, scientists claimed that the world’s “races” had different “origins” and were therefore different “species”. Photo by APS Museum. CC BY-NC 2.0

Universities were essential to the development of scientific racism. For more than two centuries, from the 1500s to the 1800s, colleges and universities throughout the United States and the Americas supported research and implemented curricula that argued for the enslavement of black people, the superiority of the white man, and the inferiority of Natives and their ways of knowing. Scholars such as Josiah Clark Nott, Robert Knox, George Robins Gliddon, and Samuel George Morton among many others lived to prove that the racial inferiority of people of African, Pacific Islander, Asian, Caribbean, and Indigenous descent, justified conquering them, enslaving them, exterminating them, exploiting them, segregating them, and/or occupying their land. Be this within the newly created U.S. borders, or south of the U.S. borders, or in Africa, or in Asia, or the Pacific Islands, all regions colonized by Europe and/or the U.S. during the 17th, 18th, 19th 20th, and 21st centuries. In arguing white superiority, these scholars measured the skulls of diverse populations, put forth theories of polygenism supporting the classification of human populations as distinct races stemming from different origins, and spoke of the “primitive psychological organization” of slaves. Their research and the value given to it by way of the university institution made it possible to create the logic for the colonization and occupation of vast territories and peoples during the forming years of European and US imperialism world-wide.

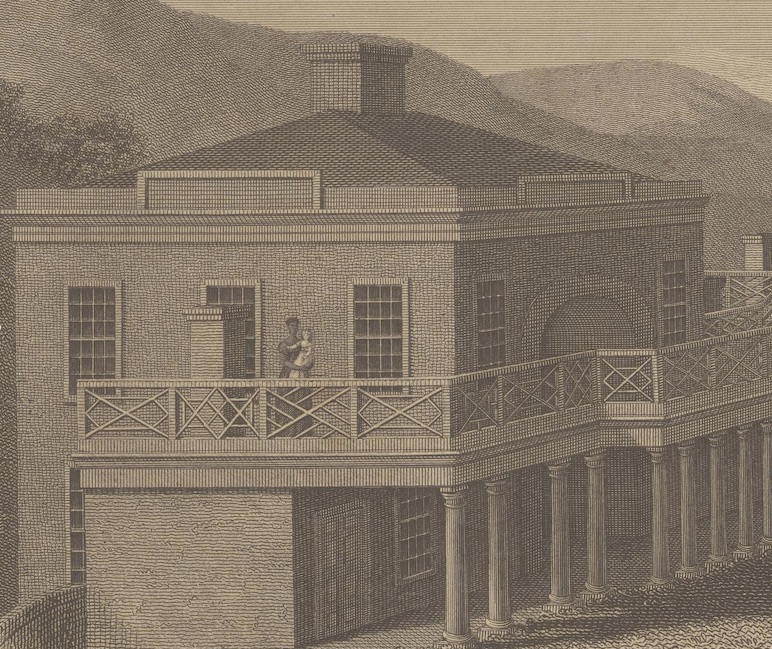

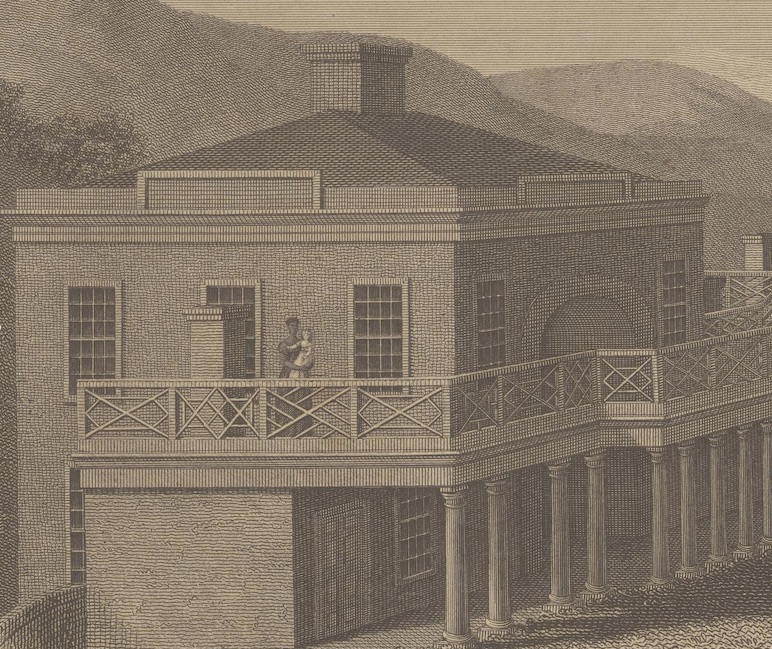

Universities both in the North and South of the United States participated in the economy of slavery. As scholar Craig Steven Wilder’s work most recently demonstrates (Ebony and Ivey, 2013), in the South many colleges owned and used enslaved blacks to build and maintain university campuses. Fully at the disposal of the universities that owned them, campus slaves were forced to commit their labor to the campus which held them. They served the students, the faculty, and the administrators. Slaves took care of administrators’ and faculties’ children, rang campus bells, prepared meals, cleaned students’ shoes, made beds, obtained the wood for fires, and tended farmland owned by administrators and universities. In some instances, students, administrators and faculty even paid special fees to their respective university to be able to bring their personal slaves to campus. Yale, Columbia, Harvard, Brown, and Princeton among many other prestigious universities of the North, were no. These institutions suitably accepted into their student body the sons of wealthy slave-owners, including sons of wealthy slave-holder elites from the Caribbean (Wilder)[i]. Both directly and indirectly, universities all throughout the nation supported the economy of slavery, benefited from it, and played a crucial role in retaining the racist and racial order of things in the newly created white settler nation.

Engraving from 1827, University of Virginia. Female slave carrying baby. Zoomed in image of Rotunda and Lawn, B. Tanner engraving from Boye’s Map of Virginia from the University of Virginia Library Materials.

The sons of plantation owners who studied in Europe were seen as experts on Natives and enslaved Blacks because of their close contact with them (Wilder)[ii]. Insisting on the economic benefits of slavery while also furthering the case for U.S. genocidal politics at home, these slave-owners’ sons wrote entire dissertations and gave lectures on the physical and intellectual inferiority of these groups (Wilder)[iii]. Their work’s objective was to dehumanize their subjects or rather objects of study. Their lectures not only helped validate and explain the system of racist economic, social, and political rule in place in the U.S., it also argued for its perpetuation.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Blacks and other people of color in the U.S. as well as Jews and non-Protestant Christians were still not admitted into universities. Black colleges and universities were created for this very particular reason in the 1800s. Throughout the U.S. students of color were not legally allowed into higher education until the second half of the 20th century. That is approximately 50 years ago.

The very university from which you graduate today was founded in 1888, just a few years into the occupation of the Puget Sound area by its white settlers. Even though the area began to be “visited” by English “explorers” in the late 1700s, permanent European settlement was achieved in this region in 1852 when a Swedish man by the name of Nicholas De Lin discovered there was lots of money to be made by exploiting the area’s lumber. The Nisqually and Puyallup regional tribes fought back and in 1855 the settlers were forced to flee, being able to return only after Native populations of the area were put in a nearby reservation by the U.S. government, leaving the Puget Sound area free for its exploitation by the returning settlers. Founded in 1888, our university is directly and indirectly a product of this occupation.

But just as these academic institutions have historically wanted to make you and your bodies of color invisible, there is also a long history of struggle for visibility, inclusion and the right to existence that precedes you; one that also dates back to more than 500 years ago; from Native and slave rebellions, to organized walk-outs, hunger strikes, sit-ins, street protests, to people writing our own excluded histories and creating spaces within academia so that you and I could learn about our own histories and struggles as well as recuperate lost ancestral knowledges. Many students and educators before you even paid with their lives for you to be able to be here today; for you and I to be here today and to celebrate you. During the 1960s young women and men fought the police, racist administrations, went to jail and sacrificed spending time with their own families to create the possibility for you to be able to get the very degree that will soon be in your hands. Your immediate communities and families have also sacrificed a great deal and gone through many difficult moments in life in order to make this day a reality for you. I sincerely congratulate them on this day, only your parents know all the struggles they have endured to make this day possible for you.

During your time at the University of Puget Sound all of you graduates have pushed and struggled and studied late nights and long days to arrive here and you made it to graduation. But always remember that you are exceptions. Despite us now having an educational system that is color-blind in theory, Blacks, Latinos, and Natives specifically, continue to be under-represented among those making it to college and graduating with bachelor degrees. In high schools, Latino and African American students nationally are disproportionately represented at every stage of the school-to-prison pipeline and only 53% of Native students graduate from high school [iv]. In today’s corporatized university system moreover, students of color are shouldering the most student debt, disproportionately higher numbers having to drop out of college because of the economic burden that academia now represents. You graduating from here today is that much more symbolic because of all of this.

But I want you to know you have a long road ahead of you. Twenty years ago a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor of Science degree held a lot of weight; it was an accomplishment. Today it is still an accomplishment but it does not carry the weight that it once did. So therefore I urge you to go further; I urge you to go get your Masters and your PhDs, to continue your education in one form or another. And I challenge you once you’re out of these spaces to create opportunities for those in your communities of origin. Too many in our communities who make it to far places too easily forget their origins; choosing to distance themselves from their communities and their own community’s history of struggle and survival. I urge you to not be one of them.

I wanted also to tell you you’re definitely not graduating from this institution with just a Bachelor’s degree. By now you all have a PhD in surviving and knowing these dominant white spaces of power that you will continue to navigate after graduation; these are places that will continuously try to shape and mold you and your spirit; dictate who you should be; what you should think; where you should go in life. The University of Puget Sound, while not always the most welcoming space for students and people of color, does in my mind do something beautiful. It challenges you and in doing so prepares you for what is to come ahead. Consciously or unconsciously you’ve met this challenge. While here, the dissident, non-conformist, rebel in you learned how to create what bell hooks would call our own communities of resistance to spaces that in subtle and not so subtle ways too often told you: “you don’t belong here”. That resistance may have looked different for every one of you. For some of you it looked like student activism on social justice related issues, building solidarities between students of color, while for others it may have been selecting particular friendships; or choosing your mentors or simply knowing when to seek spaces away from whiteness. While here, consciously or unconsciously you managed to create for yourself communities that helped you find your way through the daily micro and macro aggressions, the assumptions, the presumptions, the comments inside and outside the classroom, the burden of having to explain yourselves and your experiences –all the time–, the loneliness, the alienation, and yes, the depression. While here, the dissident, non-conformist, rebel in you pushed you to create communities that allowed you your voice whenever you needed to speak, yell and cry; to create communities that also allowed for your silence whenever you didn’t feel like speaking, yelling or crying. While at Puget Sound, the dissident, non-conformist survivor of 500 years of colonization in you also learned to question that which you have been taught in the classroom; that which you read in color-blind texts presenting themselves as universal knowledge.

So you leave here knowing when to separate useful knowledge from that which will not serve you, but further estrange you and worse, assimilate you into what the dominant culture wants of you, thinks of you, and desires of you. There is therefore very little I could advise you today in this art of survival you all know very well and have PhDs in by now. The art is actually now more than 500 years old, passed on to us by our ancestors, our parents, and the collectivity of our resisting spirits.

What advice I can offer however is to not ever let the resister and creator in you be silenced; if you spoke too soft here, amplify that voice; if you found your voice here, solidify and strengthen it. If you feel you are still in the search of your voice, be compassionate and honest with yourself, your interests, and your passions. Dream big and in following those dreams be as persistent as you can be and do not give up or let others take you in different directions.

Be creative. The world that awaits you out there is at times too ugly, too vicious; too inhuman. It is a world replete with racism, fear of your bodies, a world continuously in crisis and at war; a world submerged in a neoliberal economy that thrives on the imprisonment of bodies of color, war, forced migrations, the continued destruction of our mother earth, and the commodification of absolutely everything including love. This is a world that too often will seem to leave little to no air to breathe. So please go out and create your own breathing spaces. Continue in the creation of resisting, loving communities because you didn’t and don’t ever get anywhere on your own. As our Native sisters and brothers will always remind us, we are all connected to communities that transcend time. We’re connected to the first ancestors who walked the earth; to their struggles and their deeds. But we’re also connected to those who are not yet here, those generations who will be born tomorrow and thereafter; those who will walk this earth in the future long after we’re gone. Our job in the middle is to bridge the gap, take on the inheritance from our ancestors and our past, add our own deeds, our struggles, and leave this a better place for those that will follow. The responsibility, to say the least, is tremendous.

So make yourself and your communities visible. Resist becoming invisible; and resist becoming that which others and dominant spaces want you to become; resist it with all of your passion, your love and your humanity. Stay connected and grateful to those who’ve helped you and loved you along the way and those who will continue to be there for you. And give back.

Above all, don’t ever forget we were never meant to be here celebrating you today. Love you all.

Notes

[i] Information based on Craig Steven Wilder’s excellent book on the subject of universities and slavery, Ebony and Ivey (2013). I highly recommend this read.

[ii] From Wilder’s book Ebony and Ivey (2013).

[iii] From Wilder’s book Ebony and Ivey (2013).

[iv] “Tolerance in Schools for Latino Students: Dismantling the School to Prison Pipeline”

From The Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy, May 1 2015.

Oriel María Siu is Assistant Professor and the founding Director of Latino Studies at the University of Puget Sound. She earned her PhD from the University of California, Los Angeles; her Masters from the University of California, Berkeley; and her BA degrees in Chicana/o Studies and Latin American Literatures from California State University, Northridge where as an undergraduate she was involved in the establishment of the first Central American Studies Program in the nation. Her research and teaching interests include contemporary Central American cultural productions from the diaspora, de-colonial border thinking, Latina/o cultural productions and diasporas, and narratives of race and racisms in the US. She has published several articles on these topics and is currently working on her book on novels from the Central American diaspora. Siu is also a mother and a dancer. She is from San Pedro Sula, Honduras and lives in Seattle, Washington.