May 13, 2013

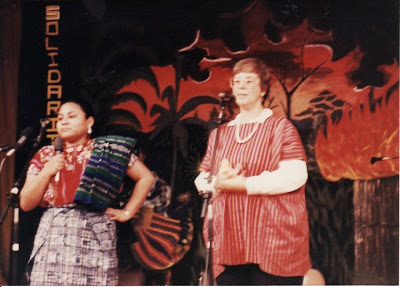

Guatemalan activist Rigoberta Menchú visits Los Angeles, CA, and tells her story at an event organized by the Guatemalan Information Center. Norma Chinchilla, the author’s mother, translates. Circa 1982. (Photo courtesy of Maya Chinchilla.)

“Knowing the truth may be painful, but it is without any doubt, highly healthy and liberating” –Slain Guatemalan Bishop Juan Gerardi, 1998

In the 1980s, my parents and a group of Guatemalan exiles founded the Guatemalan Information Center, a human rights and solidarity organization focused on international solidarity with Central America. They showed documentaries like When the Mountains Tremble and slide shows to raise awareness about the extreme human rights violations in Guatemala, which were enacted with the complicity of the U.S. government under the Regan administration. They spent nights and weekends organizing events and staffing literature tables all over Los Angeles, often accompanied by guest speakers, music, art and food. I vividly remember the leaflets and flyers, permeated with the smell of mimeograph ink, and small newsletters that they learned to typeset themselves. Like other dedicated organizers, my parents didn’t have a regular bedtime. I remember my sister and I found places to sleep in corners of the room when meetings would go on late into the night. I have written about this experience in my poem, “Solidarity Baby,” in which I call my home a “Central American underground railroad,” or a place where refugees and exiles rested after running for their lives.

I grew up hearing about dictators such as Jose Efraín Ríos Montt, a cruel army general who, after leading an internal coup became the de-facto president in 1982. He is only one of many U.S. supported military regimes that took leadership after the years following a U.S.-backed military coup in 1954. This same general and former president was recently on trial for crimes against humanity and for helping to design and execute the scorched earth policy that resulted in the Maya genocide during the 1980s, the most brutal period of Guatemala’s 36-year war. This historic trial marks the first time a former head of state has been convicted of genocide in his own country and is the result of years of struggle from many, like my parents, who never thought they would see this day.

I was five or six years old the first time I saw When the Mountains Tremble, a powerful documentary about the repression of indigenous Guatemalans by the military dictatorship and the ways in which Mayan and Ladino Guatemalans organized themselves to resist repression and to work for much-needed fundamental social and economic reforms. We watched it in my living room, where organizers and friends sat on couches, folding chairs, and even on the floor and leaning up against each other in anticipation of the story of the film. As a dreamy yet observant kid, tiny for my age, I would casually slip in and out of the room without much notice. Curled up in my mother or my father’s lap, I would listen to the rise and fall of their breathing, their hearts pounding as their words echoed through their chest discussing the issues at hand.

Then there he was, Ríos Montt, his face huge on the screen, smiling, overly confident, invoking the name of God and talking as though Jesus himself had blessed his crusade to protect the US and Guatemalan elite interests from the poverty-stricken masses. What I remember most vividly from the film was the sound of the military helicopters: chocka chocka chocka chocka. They were the same grayish green ones I saw in the TV show M.A.S.H. and in movies about the U.S. military in Korea or Vietnam. I still jump at the sound of thunderous helicopter blades, not because of their use by police in Long Beach, where I grew up, or in the Bay Area, where I now live; it is because of images and sounds of helicopters used by repressive armies against Mayan villagers that are so deeply engraved in my memory.

These memories come in bits and pieces, but what is always present is the feeling of anxiety, the intensity of the silences, the power of the personal testimonies, and the sense of the life and death urgency of the times. While I may not have understood the complexities of dictatorship, repression, organized resistance, and the U.S.’s assistance to authoritarian governments at a young age, I did understand that there were things that should not or could not be said at school or with other family members because they might not understand or, worse, might think of us as “commie sympathizers” and potentially disclose things that might endanger others’ lives. These included horrific stories of torture, mutilation, death squads, disappearances, and images of bodies left in public places—that is what happened to people who spoke out, and this filled me with fear. Of course, there were stories of heroism and bravery and stories about the importance of individual sacrifice for a better life for future generations. Yet the images of repression were so powerful they accompanied me as I went back and forth from the refuge of my home into the world.

At times I feel I absorbed my parents’ anxieties and none of their political training or coping skills. This is the trauma that I believe has been inherited by many of us who are second-generation Central Americans, who were either born over there and left very young or born in the U.S. like me, who did not experience the violence first hand. The impact of the war lives on in our silences and is only healed by knowing the truth, telling our stories in all their complexities and cultivating our creative imagining of a more just and boundless future.

It was not until I had the opportunity to research and write about my family history in college that I was finally able to articulate the weight I had felt all my life and the urgency to put the pieces of my memory together. I found other Central American students—or rather they found me—the majority 1.5-ers who came very young from Guate or El Salvador, who shared their stories and asked me about mine. It was the first time people asked me questions about what I thought about my identity and history and the first time I felt they wanted to listen. I read Central American, Chicano/a, Puerto Rican and other Latin American poets. I found myself in the margins between Spanish and English. It was then that I first wrote a poem called “Central American-American,” yearning for my own cultural movement to find names for this 2nd generation experience.

As Guatemalans are apt to do with their corny and dark multilayered humor-coping mechanism, I often joke about our collective skittish Central American paranoia or the worry, the caution, the mistrust: the way I was taught to always know where my shoes were at night in case we had to just get up and go; the lectures from my parents on how to answer the phone and who was allowed to pick me up at school; my training to remember specific numbers for emergencies, to avoid saying too much; that everyone was shady until proven otherwise and the way every time we went to Guate, I was told that being too “Gringa” could get me in trouble, but how the act of forgetting and not asking too many questions could also keep me safe. Some of this was the usual conversation for cautious parents to have with their elementary-school-aged, latch-key kids, but I knew for us it was more than that.

Today, just hearing any little thing about Guatemala in the news as a 2.0 Chapina causes my body to tense in places. Some of that tension is actually excitement that we will finally be able to hear more of the truth, that others will understand our collective intensity around the need to know more, the hunger to find justice and move beyond only speaking of the violence to never forget, so as to never let it happen again. And now, more recently, I continue to put the pieces together when I share my writing with others and show my own students’ documentaries like When the Mountains Tremble. Showing films like this one still cause me anxiety and sadness; but, more than anything now, I choke up with emotion when I think about the incredible strength and resiliencies of those that have survived to tell these stories.

I still remember the sound of the Quiché-Maya accented Spanish of Rigoberta Menchú, the young narrator of the documentary, with her bright, focused eyes and hands folded calmly in her lap. Her words were interspersed with the sounds of the boots of the fresh–faced, idealistic guerilla fighters, mostly indigenous men and women, hiking through the mountains, sharing their dreams about the more peaceful and humane world they hoped to create for future generations. I remember the deep baritones of the cocky generals explaining the importance of resisting the supposedly Cuban-influenced “subversives” and the face of the often Mayan-descended young military soldiers with their M-15 rifles, looking like they could be the children or brothers of the dead villagers and the wailing mothers.

It is with the same combination of pride and deep sorrow that I watched the trial against Rios Montt, an unprecedented historic event, in which survivors of the violence and genocide, along with hundreds of expert witnesses, have been documenting their stories and presenting evidence for crimes against humanity in a court of law and as a matter of public record, in hopes of finally bringing the perpetrators of the violence to justice.

There have been many moments of frustration and dramatic attempts at disrupting the proceedings of this trial. But the trial and what it symbolizes for so many people in Guatemala and outside the country who have remained persistent—from those who experienced the violence first hand–to the documentarians, the forensic investigators, the writers, the scholars, the organizations such as the ones my parents were involved in—this day feels like a small yet definite triumph. One of the most powerful moments of the trial came when more than 30 Mayan-Ixil women, with their heads half covered in traditional weavings to protect their identity, testified in court to the systematic rape they experienced and witnessed, the dismemberment, murder of children, family and wiping out entire villages. They had survived to tell the truth and were willing to continue risking their lives to do so.

This trial is not about revenge. Nothing can bring back the dead or heal the trauma inflicted upon a generation of people. Instead, this is an opportunity to record the truth as public record in a Latin American country that has never witnessed anyone brought to justice within its own borders, where perpetrators continue to act with impunity. This is an opportunity to break the silence, however long it takes, to declare, as has been repeated over and over: Sí hubo genocidio. Yes. There was a genocide in Guatemala.

As physically and emotionally hard as it has been to write this, I feel that by telling my story, I access a ounce of the strength of the many people I saw give their personal testimony over the years. This is an act of bearing witness, telling you, “I experienced this with my own eyes.” It disrupts the silences and the official stories that seek to erase the personal toll, each of the individual human beings and their suffering. It also testifies to the generations of colonial violence and racism that continues today. Finally, it accounts for the feelings of madness that come along when you are obsessed with telling the truth and hoping someone will hear you; hoping that more people will act, yet realizing that you can’t wait for anyone to tell your story for future generations. So many overwhelming feelings after the announcement that Rios Montt has indeed been sentenced and found guilty. After so much time and so much struggle I feel a sense of a momentary relief, a moment of justice after so much sorrow and loss at such a high human cost. All this fighting for truth, reconciliation and justice has not been in vain.

BEFORE THE SCALES, TOMORROW

By Otto Rene Castillo

(Guatemalan Poet of the Committed Generation)

And when the enthusiastic

story of our time

is told,

for those

who are yet to be born

but announce themselves

with more generous face,

we will come out ahead

—those who have suffered most from it.

And that

being ahead of your time

means suffering much from it.

But it’s beautiful to love the world

with eyes

that have not yet

been born.

And splendid

to know yourself victorious

when all around you

it’s all still so cold,

so dark.

Maya Chinchilla is a poet, filmmaker, and educator, who has taught English at the Peralta Colleges and Latina/o Studies at San Francisco State University. Currently, she is working on her first poetry manuscript for Kórima Press. www.mayachapina.com

Comment(s):

-

Maya Chinchilla May 13, 2013 at 1:54 PM

Links for more information:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dOIJ1-7LDQs

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/11/world/americas/gen-efrain-rios-montt-of-guatemala-guilty-of-genocide.html?_r=1&

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-22490408

http://www.riosmontt-trial.org/

http://boingboing.net/2013/05/09/guatemala-i-am-innocent.html -

Miriam May 21, 2013 at 1:01 PM

thank you for writing this, maya. putting together the puzzle of who you are. where you come from. the mountain trembling weight your name hefts. linked to the blood chilling images from the dictator’s trial. all power to the women & men of fire and heart who would not be silenced or shamed. wishing them & their babies & their dreams bulletproof protection. wishing you love & delight in your newfound voice. xoxo, miriam

-

Anonymous May 14, 2013 at 1:55 AM

Yes indeed! No matter what happens after this conviction was delivered in the case of Genocide in Guatemala, or whether more political recourse will be waged as a tool for perpetual impunity in Guatemala, many facts will remain true no matter what. One of them, the VOICE of Guatemalan Mayan women were spoken and heard across the world. A testament to the courage of Ixil women, proof that not even genocide was able to silent them. -

¡Exactamente! No importa que pase después de esta convicción en el caso de Genocidio en Guatemala, o qué otros recursos técnico legales son usados como herramienta para perpetuar la impunidad en Guatemala, ya que los hechos son auto evidentes sin importar que hagan. Uno de estos hechos es que las VOCES de la mujeres Mayas guatemaltecas hablaron y fueron escuchadas en todo el mundo. Como testamento de la valentía de la mujer Ixil, prueba que ni siquiera el genocidio pudo apagar sus voces.

-

Sonia May 14, 2013 at 12:48 PM

beautiful, honest, sad, joyful, history, beautiful

-

Unknown May 14, 2013 at 1:19 PM

Maya, thank you. Thank you for existing as you are, and for openign to the sharing of your story. Please, keep story-ing.

This piece left me speechless, and streaming sweet tears of sorrow amongst the genocide that ravages the Americas. I am grateful for the soul-heart-psychic-work you do daily, breath by breath, cuz it seems necessary to nourish the courage and genius required to weave together words as story as reprieve and inspiration to keep struggling, such as you have here.

Also – I’m in a PhD program in Urban Planning, a place where I am exploring genocide in the Americas. That institutional program has been a seed for something else, a parallel universe Planning as Poetry PhD program, that is being birthed with coaching by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and in collaboration with other folks. Right now, our workshops are exploring forced movement in relation to settler colonialism and being 1.5ers living in the U.S. I’d love to share this piece for us workshoppers to read together. THANK YOU!

-

Anonymous May 14, 2013 at 11:28 PM

On Friday, May 10, when Efrain Rios Montt’s verdict was read, Judge Jazmin Barrios stated: “The crime of genocide affects all Guatemalans, because it damaged the social fabric of the country.” The genocide, Barrios added, caused multi-generational pain, trauma and damages. And it is this multi-generational impact of the genocide that my colleague and friend Maya Chinchilla eloquently expresses in her essay “Chapina 2.0: Reflections of A Central American Solidarity Baby”. Gracias!

-

Pamela Yates May 15, 2013 at 8:57 AM

Maya, it is so gratifying to know that our film WHEN THE MOUNTAINS TREMBLE had this effect on you and helped make you the wonderful woman, the writer you are today. I wanted to let you know that WHEN THE MTS. TREMBLE and GRANITO DE ARENA (the sequel) are now streaming online free on PBS in both English and Spanish right here.

http://www.pbs.org/pov/granito/watch-when-the-mountains-tremble-online.php#.UZOvviv72K8

We’re doing this to commemorate the guilty verdict for Ríos Montt. We also have put up filmed moments from inside the genocide trial DICTATOR IN THE DOCK right here

http://www.granitomem.com Please get in touch with me. I want to know you. Pamela Yates, Director, “When the Mts. Tremble” pamela@skylightpictures.com -

Clarissa Rojas May 17, 2013 at 1:51 PM

you brought us into the living words of witness.

Ixil woman says during the trial: “even assuming that the General Rios Montt stays in jail, he will be fed every night, what about us? We still have to worry about whether we will die of hunger.” this is a historic moment on which the work to address the legacies and continuities of colonial and neo-colonial violence in Guatemala builds. the mic is turned way up on the everyday enactments of genocide and feminicide. solidarity starts with gesturing toward listening. gracias maya. may all the words that beckon to be spoken arise and guide the tasks before us all. -

Luz Vazquez-Ramos May 29, 2013 at 8:01 PM

Well done Mayita! Keep telling your story.

-

MARLENE LEGASPI June 20, 2013 at 11:25 PM

I always feel blessed when I have an opportunity to read another person’s words and how they depict such an immovable, intricate and complex aspect of their experience and identity. I really appreciate you pointing to trauma children retain into adulthood when much of their residual emotions may be based on memories and the stories they were told. My mother once told me during WWII that a special siren would go off when she was a little girl in grade school informing everyone that the Japanese military were coming to abduct children to force them into sexually slavery, and how routine it was for them to hide and when I remember her story the exact emotion I had from such a visceral account comes right back to me, as if it ever really left. But thank you for sharing this! Thank you.

-

Cyber Chapina June 27, 2013 at 6:29 PM

I want to thank you all for your own powerful comments, for reading and sharing this essay, for the encouragement and incredible response, and to MALCS Mujeres Talk blog for the editorial support in the writing of this piece. Although the trial has been partially annulled and is for the time being on hold, I still believe all this work and sacrifice has not been in vain. I originally wrote this not knowing what the out come would be but still with the urgency to write and put these pieces together.I was hesitant in my own celebration but found it necessary to celebrate each victory no matter how big or small, no matter how many steps forward or back we may feel this process has taken all of us. The resilience of those who continue to fight for justice remind me that there are those of us who can not give up. Failure is a luxury. Survival is a victory in and of itself and our cultures and people deserve to heal, thrive in order to change the status quo. Please keep an eye on this important international in internal work being done in Guatemala as well as supporting the diaspora in telling their stories too. Un abrazo. http://www.riosmontt-trial.org/

-

Roberto Lovato July 4, 2013 at 2:49 PM

A few months after you shared this piece,I finally took it out of bookmarks and read it. Well done, Maya. Helped me better understand the tragi-heroic drip of our very violent, very inspired political legacy on the 1.5-2.0 generations. Difficult but necessary to write. I hope it inspires other young people to write because Gerardi was and is write about painful truth. Was glad to see the pic of yer Mom w/ Rigoberta. Thanks for writing and sharing. Un abrazo, R