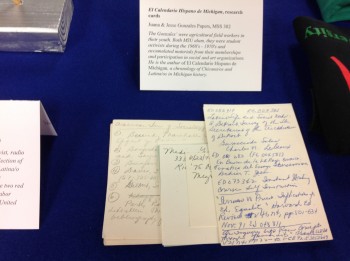

Documents from El Calendario Hispano de Michigan, from The Papers of Juana & Jesse Gonzales Held by Michigan State University Library

By Diana Rivera

Dr. Christine Marin’s (ASU) January essay here on Mujeres Talk brought attention to the work she and other Chicana/o and Latina/o archivists and librarians performed in building collections that document the history of our communities in the Southwestern US (21 January 2014). It brought to mind the fact that Mexican and Puerto Rican communities have also, for the past 100 years, been in areas beyond the Southwest and East Coast, including the Great Plains, the Pacific Northwest and in particular, the Great Lakes region. Their stories, their lives and sometimes their contributions have been documented through independent, government and academic narratives, reports, demographics, statistics and historical studies. Scholars such as Paul Schuster Taylor, Norman D. Humphrey and George T. Edson have written on Mexican migration and immigration to region while Lawrence R. Chenault, Clarence Senior and Abram J. Jaffe surveyed and recorded Puerto Rican migration early on. This work charted our migration routes, our living conditions and early settled-out communities. They also studied our labor and dependability patterns and sometimes touched on culture, tradition and history. None of these types of studies relied on the kept materials, keepsakes or oral histories of the Mexican and Puerto Rican communities. Instead, these reports and statistics provided a sanitized narrative of our growing presence in the early years.

Even though it should not fall only to Chicana/o or Latina/o librarians or archivists to build a Chicana/o-Latina/o Studies (CLS) collection, more often than not, it does. Regrettably, the number of Chicana/o and Latina/o graduates from Library & Information Science Degree Programs are not keeping up with a growing Latina/o population in the US. Dr. Marin’s essay prompts the question: What is being done to preserve and conserve the history of Chicana/o and Latina/o communities not only in, but also OUTSIDE of the Southwest?

Internationally known Chicana/o-Latina/o Studies (CLS) librarians Dr. Christine Marin, Margo Gutierrez (UT-Austin), Lilly Castillo-Speed (UC Berkeley), Dr. Richard Chabran, Dr. Maria Teresa Marquez (UNM) and Nelida Perez (CUNY) laid the groundwork for me and my peers at libraries across the country to emulate. My predecessors, and some contemporaries, in libraries and archives who have built excellent collections have established a model that I have followed to develop and to build collections that document Chicana/o, Puerto Rican and Latina/o stories in the Great Lakes Region. These materials are now available for scholarly research, including government reports and academic work.

In a January comment on Dr. Marin’s essay here on Mujeres Talk, I noted that one of my first areas of responsibility as a new librarian was working with a small collection of maps stuck in the back of the Art Library at the Michigan State University Libraries (MSUL). As one of maybe two librarians of color there, I felt an affinity for this format, which seemed so out of place in a collection composed primarily of monographs. I was asked to take on Mexican Studies (mostly because I was of Mexican heritage) but went “rogue” by buying more titles on Chicana/o Studies than what was established in our collection development policy. In 1995, Chicana/o and Latina/o student protests on campus led to the university creation of a space honoring Cesar E. Chavez. The Cesar E. Chavez Collection is a multi-format and multidisciplinary collection on the life of Chavez, as well as the Mexican American and Puerto Rican presence and experience in the US. With the assistance of Chicana/o and Puerto Rican students, we developed a healthy CLS collection unselfishly guided by Margo Gutierrez, the Mexican American and Latino Studies librarian and bibliographer at the UT Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection.

Our “multi-format” collection was initially a small collection of ephemeral vertical file material like flyers, brochures and newsclippings. It served a minimal role in the writing and teaching that students and faculty were doing on local and regional subjects in Chicana/o and Latina/o Studies. Instead, researchers were finding the histories, accounts and statistics in texts or in manuscript archives back in Texas, the rest of the Southwest and Mexico. There was little collected at MSUL that provided researchers with regionally unique or unpublished materials by organizations or individuals about local activities, including correspondences, speeches, pamphlets, agendas or meeting minutes. It was an apparent need and challenge to start archiving our history in Michigan and the Great Lakes region. Although our language, culture and traditions pulled our hearts back to the Southwest, Mexico and Puerto Rico, our families, our memories and our stories began within the Great Lakes, Northeast or Great Plains regions. Now that we have more than a 100 year presence in these regions, it becomes more than important, actually critical to start gathering the histories and experiences of early Latina/o communities in “el norte,” histories beyond the popularly understood geographic boundaries of “Aztlan” and Borinquen.

Collections of note that have included Chicana/o and Latina/o voices and materials are relatively new. These include the holdings of the University of Iowa Libraries Iowa’s Women’s Archives with the Mujeres Latinas project that includes the papers of 15 families dating from 1923, over 80 oral histories of Latinas/os, organizational records dating back to the 1960’s and other related collections; the University of Michigan Bentley Collection with a growing number of personal manuscript collections (6) and organizations (3); Hope College (in Holland MI) with an early collection (1970s) of oral histories (many transcribed) and the MSUL Jose F. Treviño Chicano/Latino Activism Collection with 18 manuscript collections (processed) with content dating to the 1940s. Our small vertical file at MSUL developed into the manuscript collections of donated papers of Mexican American community members in Michigan. These collections now include photography, political buttons and other ephemera.

Although the manuscript collections donated by Michigan families are nowhere near the volume of those collections found in the Southwest (or now the Northeast at the CUNY-Hunter College Collection), they have provided a starting point for researchers focusing on Latina/os in the Great Lakes region to learn about the presence of Chicana/o and Latina/o communities dating back to the early part of the 20th century.

Collections that encompass the range of eras, locations and subject matters that will provide a one-stop source for researchers inquiring about Latina/os in Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana or Wisconsin are hard to come by. However, we as librarians and archivists are at a pivotal point in time when the student activists, community leaders and closet archivists of the 1960’s no longer need or want their collections of papers, documents, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, scrapbooks, garage-printed-mimeograph machine of the ’60s chapbooks and publications, flyers, bumper stickers, buttons, posters and bandanas or t-shirts. Some potential donors are not ready to entrust materials to an institution to which they have no history, affinity or connection. Some are fearful that their long and carefully collected materials will be seen as unimportant or tossed. Others do not see their materials as important enough to donate or do not remember what is in their own collection that may unify or supplement the papers found in the collections of others. And then some do not know how to approach an institution about archiving their materials or are confused about their ownership and access rights.

For academic or family archivists seeking a location to deposit or donate their teaching and research materials, or family papers consider these simple rules:

- Donate: Libraries and archives accept materials given to an institution. Once donated, materials become the property (except for the intellectual property rights / copyrights, which may be negotiated) of the institution. A signed Gift Deed is important with the conditions of ownership transfer and possible tax deduction opportunities clearly listed.

- Access and Restricted Access: Who can view materials, what they can view and when they can view them depends on the condition of the material, the institutions’ policies regarding use and duplication, the library speed in processing materials for public use, as well as any restrictions donors create on sealing sensitive materials for their and others’ protections for a specified number of years.

- Copyright: May be legally transferred to heirs or others.

- Inventory: The organization and inventory of donated materials is critically useful. It provides staff a useful guide to work from, limiting the number of hours required to process and make the manuscript collection available.

- Storage Expectations: The institution should re-house materials into acid-free, preservation quality boxes, folders, preservation sleeves (for fragile or aged material) and apply appropriate curation methods.

- Monetary Donations: These are not a condition of having ones’ papers accepted by an archive. However, because many libraries and institutions are non-profit organizations, they might welcome any donation — if one has the means — to be applied to the processing of donated materials.

- Find an Information Specialist: If you do not know of or can’t find an institution in your community to best help preserve and document our history, please do not throw it away. Please. Reach out to an information specialist (librarian, archivist or even a professor) for guidance, or even a Mujeres Talk editor, for help on where to place potential material donations.

Diana Rivera is the Chicana/o Latina/o Studies Subject Specialist and Head of the Cesar E. Chavez Collection at the Michigan State University Libraries.