By Dr. Christine Marin

Chicano and/or Mexican American student activism during the era of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement was the “mother” of that creation known in 1969-1970 as Chicano Studies Collections, usually housed in university library departments called Ethnic Studies or Archives and Special Collections. Since then, the southwestern states of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas have seen the rising interest in the research and scholarship of Chicana/o, Mexican American, Hispanic, and Latina/o students and faculty, and others of course, who continue to press their libraries to collect and house primary and secondary sources in Chicana/o and Latina/o Studies. For example, the Chicano/a Research Collection at the Hayden Library at Arizona State University; the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the Library, University of Texas-Austin; the Chicano Studies Library at the University of California-Berkeley; the Chicano Studies Research Library in Los Angeles; and the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives at the University of California-Santa Barbara have enjoyed great success in the decades following the Chicano Civil Rights Movement.

Archivists at Chicana/o and Latina/o repositories and university libraries seek to document and protect the rights of these cultural communities by capturing their collective memories. Through these efforts, we work to ensure access to Hispanic/Mexican/Mexican American and Latina/o histories and expand future opportunities. We work, in short, to preserve these legacies for students, faculty, researchers, writers, and scholars today and in the future. It is easy to understand why it is the duty of the archivist to value and appreciate the complexity and diversity of Mexicana/o and Latina/o communities and to collect, preserve, and make accessible materials that are representative of their culture and history. Materials acquired are often unique, specialized or one-of-a-kind. For example, they might be rare legal or business documents in Spanish; or written letters that describe life experiences across the U.S.-Mexico border; or marriage, school or religious documents of the late 1890s or early 1900s. They are to be preserved for use today and also for future generations of researchers. They are to be protected from theft, physical damage, or deterioration. It stands to reason that Chicana/o and Latina/o archival repositories are now the intellectual gate-keepers of cultural knowledge with archivists playing a significant role in their university’s ability to attract and retain Latina/o faculty and students.

At the Society of American Archivists’ (SAA) Annual Meeting at the University of California in Los Angeles in 2003, a pre-conference event titled Memoria, Voz y Patrimonio (Memory, Voice and Heritage) challenged participants to consider their roles as archivists and representatives of local communities in Chicana/o and Latina/o Studies. The gathering addressed questions about the acquisition, preservation, and maintenance of archival materials in light of new technologies in archiving Latina/o history, identity, and spirit. Those present discussed the importance of preserving primary sources in print, but also addressed the necessity of preserving and archiving films, photographs, ephemera, broadsides (posters), videos, cassette tapes, and reel-to-reel tapes. This work requires archivists to learn new technologies, and in 2003 those at the SAA pre-conference were coping with new challenges in using computers, electronic databases and records, and other new technologies — all so that they could teach patrons and students how to access information in their archival repositories. Those of us working in Chicana/o and Latina/o archival repositories or libraries learn to interweave our duties and responsibilities in collection development, reference services, outreach, research, publishing, and service. This interdependence represents the highest level of professionalism in the work of an archivist, historian, or librarian. The 2003 SAA pre-conference made it clear, too, that financial and human resources are important tools in calling attention to the importance of Chicana/o and Latina/o archives and libraries in the southwestern region and elsewhere. That point is still important to consider today in these times of lean archives and library budgets.

Chicana/o and Latina/o archivists take very seriously their role in supporting repositories and libraries and in ensuring access to collections that house the cultural achievements and records of contributions to state and regional development of Chicana/o and Latina/o communities. They work with potential donors, community activists, labor organizers, teachers, educators, entrepreneurs, performing artists, writers, historians, and others whose personal archives provide meaning and context to their own legacies.

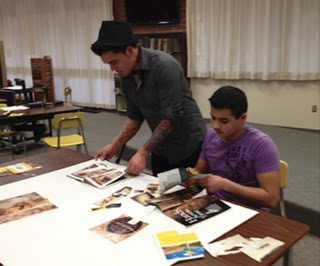

Many archivists work with local high schools and programs aimed at increasing the admission rates of Latina/o students to community colleges or universities and their success in higher education. A case in point: an archivist at an Arizona university provides workshops on oral history and methodology and helps high school teachers learn how to train students in capturing the stories and narratives of Latina/o and Chicana/o community members. The completed oral histories or filmed documentaries produced by these students and gathered by the teacher are placed in the university library’s Chicana/o and Latina/o archival repository where they are accessible to researchers and others with an interest in that community’s history. In so doing, high school students gain a better understanding of how and why their research becomes an important resource for others. Another archivist might provide orientations or tours of a Chicana/o and Latina/o archival repository to high school students as a way for them to understand the importance of using the resources in a university library and archives. In 2004, the Society of American Archivists (SAA) conducted the “Archival Census and Education Needs Survey in the United States.”[1] At least 108 Latina/o or Hispanic SAA members reported that they “learned about the value of archives from using them.” Perhaps these archivists were exposed to archival repositories as high school students and grew to understand the role they would play in their own experiences as college and university students. Today, our work with K-12 students may spur them on to want to become archivists in a Chicana/o and Latina/o collections.

There are new challenges, however, on the western horizons of Chicana/o and Latina/o history and its archives that may impact their continued availability to researchers. These new challenges are not merely financial ones. Instead, they are political challenges to Chicana/o and Latina/o communities that are also linked to the work of the archivists. In 2010, for example, new controversy and tensions surrounding Chicana/o Studies and recent legislation in Arizona makes archivists question their work in a southern Arizona high school district. Arizona’s state superintendent of public instruction said the Mexican American Studies (MAS) program taught in the public high school in an urban center violated a state law banning courses that “promote resentment toward another race or class.”[2] The school district appealed and in late 2011, a state administrative law judge affirmed the decision and the MAS program was eliminated from the public school curriculum. Elimination of a high school curriculum not only makes it more difficult for students to be successful at a community college or university level, but it also curtails a successful collaboration between the university library and high schools in collecting archival materials.

In 2010, political tensions in the Chicana/o and Latina/o communities of Arizona surrounding immigration laws began anew. Individuals of Mexican or Latina/o heritage currently represent over thirty percent of Arizona’s citizens.[3] They make important contributions to Arizona in many ways. Arizona’s history is rich in cultural diversity and its history must be preserved in order to enable as complete an understanding of the state as much as possible, yet these new tensions impact the collection of primary source materials, relationships with donors, and funding or endowment projects to preserve individual and family archives. Would monetary donations for the preservation of Chicana/o and Latina/o collections need to be returned? Are Chicana/o and Latina/o Studies programs, courses and archives all at risk? Is financial support for and use of Chicana/o and Latina/o archival repositories at these university or community college libraries also at risk?

The political ramifications of questions like these impact a wider range of constituents, archivists and major university libraries outside the state of Arizona. These risks have been met with another wave of Chicana/o and Latina/o student and faculty activism that has created fresh support for new Chicana/o and Latina/o archival repositories and programs and for new positions and appointments at major university libraries. For example, in the summer of 2010, the Chicana/o archival collection “Unidos Por La Causa: the Chicana and Chicano Experience in San Diego,” made its debut in the San Diego State University Library.[4] This Chicana and Chicano Studies Archive was created through the efforts of a committee of librarians, archivists, library staff, professors, and community activists. In another example, the California State University at Los Angeles (CSULA) Library recently celebrated the establishment of the East Los Angeles Archives to “advance scholarship in Chicano/Latino studies and Los Angeles history through the collection of primary research materials.” Other university libraries are seeking Chicana/o and Latina/o archivists to fill newly created academic positions and appointments. Their main responsibilities are to begin and build new Chicana/o and Latina/o archives in folklore, music, rare books, and manuscripts. We can see this at the University of Texas-Pan American, which offers a new archivist opportunities to engage in research and writing and to develop manuscript collections that focus on Latina/os, Border Studies, and Mexican folklore. The University of North Texas Libraries in Denton sought a Latina/o archivist to coordinate with a high-level university library administrator in acquiring new Chicana/o and Latina/o archival collections. The Mexican Studies Institute opened at the City University of New York (CUNY) with a goal of establishing Mexican, Mexican American, and Chicana/o Studies courses in New York City high schools. A Latino/a archivist or librarian will most likely assist faculty in the creation and implementation of this endeavor and begin to collect books and materials for the Institute.

At the 2012 Annual Meeting of the Society of American Archivists in San Diego, titled “Beyond Borders,” Latina/o archivists engaged in discussions and presentations about the importance of collecting the experiences of Latinas whose stories continue to remain invisible or ignored; the collection of Spanish-language primary sources to tell the history of the American West and Mexico; and the importance of collaboration between archivists on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border in order to gather research on the experiences of undocumented Mexicans in today’s politically-charged borderlands environment, one that views Mexican immigrants unfavorably.

Archivists are guided by professional core values and codes of ethics that outline their professional responsibilities. These include collection of a “diversity of viewpoints on social, political, and intellectual issues, as represented…in archival records.”[5] That is our commitment, because we know that the public will benefit from the knowledge and insight generated through study of these materials.

[1] Beaumont, Nancy P, and Victoria I. Walch. Archival Census and Education Needs Survey in the United States, 2004. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2005. Internet resource. [2] Grado, Gary. “Arizona’s Ethnic Studies Attorneys Use TUSD Officials’ Words Against Them.” Arizona Capitol Times [Phoenix, AZ] 22 Nov 2011. [3] http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/04000.html [4] “A New Chicana/o Archive at SDSU: Unidos Por La Causa.” La Prensa San Diego [San Diego, CA] 08 Oct 2010: 8. [5] http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics